‘…man is an invention of recent date. And one perhaps nearing its end’ (Foucault 1973, 387). Foucault goes on to conclude The Order of Things with the evocative image of man being erased ‘like a face drawn in the sand at the edge of the sea’. Foucault’s anti-humanism, especially as expressed in these lines, has long been considered to preclude the possibility of human rights entering his thought.

In a 1981 interview questioned on this very point – ‘Do you reject any engagement in the name of human rights on the grounds of the death of man?’ and later ‘I am wondering if it is possible to reconcile the movement in favour of human rights and what you have said against the humanist subject’ (Foucault 2014, 264-65).

It is these questions of engagement and reconciliation between Foucault and rights that Ben Golder explores in Foucault and the Politics of Rights (Stanford University Press, 2015).

‘Foucault’s curious deployment of rights’

Golder is not the first to address Foucault’s discussion of rights in his late interviews and lectures. However, he is one the first to do so without characterising Foucault as betraying his earlier critiques of the subject and sovereign models of power in order to embrace liberalism. Rather, Golder exegetes Foucault’s lectures and late interviews as a continuation of his previous work.

Foucault’s rejection of the universal human subject (The Order of Things) and critique of sovereign model of power (Discipline and Punish and The Will to Knowledge) are examined alongside what Golder calls ‘Foucault’s curious deployment of rights’.

For example, Foucault states, ‘we should be looking for a new right that is both anti-disciplinary and emancipated from the principle of sovereignty’ (Society Must Be Defended) and claims to the ‘rights of the governed’…‘a new right – that of private individuals to effectively intervene’ (Confronting Governments: Human Rights). Golder examines these remarks on rights as tactical and useful instruments for political struggle.

Rights as critical counter-conduct

Drawing on the Security, Territory, Population lectures, Golder argues that Foucault’s deployment of rights in the late-70s and early-80s is akin to the counter-conduct tactics used in the lead-up to the Reformation. Foucault argues that in response to pastoral practices that sought to govern or conduct the life of the church, a series of tactics were developed to counter this conduct. John Wycliffe, Jan Hus and associated Christian communities re-purposed the governmental instruments used by ecclesial authorities (e.g. scripture or community or ascetic practices) and opened the possibility for insurrection and resistance.

In a similar manner, Golder suggests that Foucault’s appeal to rights is not a late embrace of the liberal subject of inalienable rights derived from their humanness, but a ‘critical counter-conduct of rights’. There are three dimensions to this use of rights:

- contingent ground of rights;

- ambivalent nature of rights (both liberatory and subjectifying);

- tactical and strategic possibilities of rights as political instruments (Golder 2015, 23).

In conceiving rights in this manner, Golder is able to take Foucault’s late discussions of rights seriously without suggesting that there was a serious break with his earlier work. While Foucault may critique the anthropological and political foundations of rights, this does not preclude the possibility of making use of rights discourses in specific political contests.

Golder’s formulation of rights as critical counter-conduct can be read as part of a wider literature seeking to move away from tired debates over whether Foucauldian analyses of socio-political struggles are self-defeating with little room for meaningful action. Like Amy Allen (The Politics of Our Selves, 2008) and Colin Koopman (Genealogy as Critique, 2013), Golder appeals to the idea of ‘critique’ and Foucault’s relation to Kant to argue that there is an affirmative (if not normative) dimension to Foucault’s project.

Critical ambivalence of rights

In his essay discussing Kant’s “Answering the Question: What Is Enlightenment?” Foucault puts forward a notion of critique that is genealogical rather than transcendental. While the Kantian critical project sought universal structures of knowledge, Foucauldian critique is opened up via “historical investigation into the events that have led us to constitute ourselves and to recognize ourselves as subject of what we are doing, thinking, saying” (Foucault 2000, 315). Through his own historical or genealogical investigations into punishment, sexuality or subject-formation, Foucault opened up space for critical questioning of ourselves. Importantly, this ‘critical ontology of ourselves’ is not a new body of knowledge or information, but a critical ethos or attitude that is performed and lived.

Golder rightly identifies the way narratives of human rights and associated events have formed a prominent story that we tell ourselves and in which we recognise ourselves as subjects. Drawing Samuel Moyn’s historical analyses of human rights, Golder suggests a genealogical critique can reveal the contingent grounds of rights and expose areas vulnerability to contestation and reform. In this sense, Golder’s use of critique is more than a negative project. It is in the process of the critique of rights that he makes the affirmative move of re-deploying rights a critical counter-conduct.

Like the proto-Reformers who used ecclesia tools to create openings to resist the pastorate, Golder suggest that rights, as a practice of critical counter-conduct can resist governmental strategies that subjugate and govern too much. In putting forward this argument Golder stresses the ambivalent nature of rights, which corresponds to the reversibility of power relations described by Foucault in The Will to Knowledge. That is, the use of rights as a political instrument or tool is always vulnerable to co-option by the governmental strategy – a liberatory moment can be transformed into another instance containment and constriction.

To demonstrate the ambivalence Golder examines Foucault’s discussion of gay rights, abolition of the death penalty, and right to suicide. While on the one hand, Foucault was concerned that a dependence on a traditional liberal rights discourse would cede too much political ground and, as Golder summarises, leave “unquestioned (indeed, it reinforces) the powers of law, state, and medicine to regulate…the character and quality of that life itself” (Golder 2015, 132). On the other hand, Foucault recognised the danger of tactical deployment of rights as a means of merely reforming or refining the object of critique. For instance, rights-based arguments against the death penalty may serve to simply fine-tune methods of execution to account for humanistic concerns.

Rights: strategic or tactical reformulation of power relations?

While the ambivalence of rights cannot be avoided, attention to the relationship between tactical and strategic deployment is an important precaution. Following military theory, a strategy is the general plan, while tactics are transitional decisions or acts contingent on the circumstances and overarching strategy – or in different terms, tactics are to strategy what apparatus is to dispositif.

Golder, like Foucault, is concerned that the use of rights as a tactical counter-conduct will eventually be co-opted by the overarching strategy (i.e. the juridical order). And, while useful for a time, the tactical deployment remains within the strategy and may serve to further refine and reinforce its effects. Rather than remaining at the tactical level, points of vulnerability and weakness need to be exposed in order to shift and subvert the strategy itself.

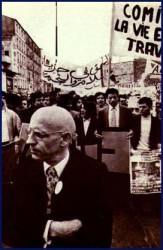

Golder cites the controversial French criminal defense lawyer, Jacques Vergès (with whom Foucault had some dealings), as an example of the way his strategy of rupture “contest the law’s legitimacy and its self-presentation so as to effect a rupture in the system itself”(Golder 2015, 125). Verges would uses the French courts as performative space to expose the French State’s criminal past (e.g. colonial violence and occupation in Algeria) and hence inability to sit in judgement on other criminal matters (e.g. Klaus Barbie, the Nazi war criminal).

In a similar way, Golder argues that Foucault’s use of rights is not merely tactical and local, but “connected to a broader and concerted strategic engagement” that skews the liberal game of state versus individual and “to inaugurate a different game, with a different mode of relation to life” that can contest the dispositif or strategic network of power. It would seem that at this point, the significance of genealogical critique returns. That is, to be able to strategically rupture and destabilise our present and our understanding of ourselves.

Golder’s argument for a Foucauldian politics of rights is provocative and productive. There are areas that I would have liked to seen explored further – especially a reading of this Foucault-as-rights-theorists in relation with other similar theorists more aligned with rights discourses, e.g. Arendt and Agamben. It would have also been useful had Golder discussed a contemporary example of rights-based politics where this Foucauldian approach could be adopted e.g. first or stateless peoples.

Golder contends that a Foucauldian account of rights “actually facilitates a range of different political possibilities beyond, and potentially critical and transformative of, liberalism itself” (Golder 2015, 62). This is perhaps the real test of Golder’s book – does this account of rights provide something that is more useful that than juridical, universal and anthropological right discourses?

References

- Foucault, M. (1973) The Order of Things, Translated by. New York: Vintage.

- Foucault, M. 2000. “What is Enlightenment?” In Ethics: Subjectivity and Truth, edited by Paul Rabinow. London: Penguin.

- Foucault, M. (2014) Wrong-Doing, Truth-Telling: The Function of Avowal in Justice, Translated by Stephen W. Sawyer. Edited by Fabienne Brion and Bernard E. Harcourt. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Golder, B. (2015) Foucault and the Politics of Rights, Translated by. Stanford: Stanford University Press.